Tags

This post was inspired by the Turba philosophorum lecture on the 4th Feb 2022

An athanor is an alchemical furnace, but what exactly does it mean in practise? And I really do mean practise because there is copious evidence for early modern alchemists building and using furnaces for their work even if we do not have such good evidence for earlier times.

(The problem here as well is that translations might not necessarily include the word athanor)

Furnaces are of course drawn in various MS going back 700 and more years but most are just square boxes and therefore not what we are after.

The Dictionary of alchemy by Mark Haeffner says

“The Arabic word at-tannur means simply an oven but the alchemical version was a very special furnace or oven pictured in the form of a tower with turret or dome roof, and its purpose was to ‘incubate’ the egg-shaped Hermetic vessel … It was supposed to preserve a constant heat over long periods, which was required to warm the alchemical egg of the philosophers, which nested in sand or ashes.”

As a general statement the above is accurate enough. The question arises though, what of the many illustrations of furnaces is actually an athanor? How is it supposed to work? And when did the word and structure actually come into use in alchemical works in general and the English speaking world in particular?

The earliest example of it’s use that I can find so far in the Oxford English Dictionary is, unsurprisingly, from George Ripley:

Thy Fornace..Whych wyse men do call Athenor.

G. Ripley, Compound of Alchymy (Ashmole MS. 1652)

The Geberian “Book of furnaces” translated by Russell has a paragraph on “On the fixatory furnace, or Athanor” which says the vessel must be embedded in ashes but this irritatingly is accompanied by the same calcinatory furnace picture as earlier in the work.

The instructions for it do not have enough information to enable us to decide whether it might be an athanor. However calling it a fixatory furnace does not seem to match the general conception of such a furnace, unless of course it was a long, reliable and consistent heat that was required to fix your materials, which usually meant oxidise them, at this sort of heat. Fixing sulphur/ spirits usually required other, lower, heats and methods. It is dated 14th century or so.

Thomas Norton’s Ordinal has a lot to say on furnaces, but does not specifically use the word athanor. He wrote about the different degrees of heat required and how he had invented a special furnace that could keep many vessels at the same heat and a similar one that could heat a lot at the same heat. Which does sound like an athanor, but we cannot be sure, especially since he doesn’t mention how long it works for without feeding with fuel. When we look at the illustrations that go with his Ordinal, it is not clear if any match the furnace that he invented. We do see quite a few that match calcinatory furnaces and distillation furnaces, but none have the tower attached which is required for feeding the fuel.

Maybe at this point I should say that the simplest way of having a furnace that heats consistently for a long period is to build it such that charcoal, ideally consistently sized, slightly rounded lumps so they don’t catch on each other, is in a central tower which has a hole at the side of the bottom, and an angled slope, so the charcoal rolls down out into the combustion area, a grid with an ash pit below and holes to let air in. Then you arrange the thing you want to heat at the right distance from the burning area, maybe using something to block off some of the heat so just the right amount gets through, then you are sorted. The tower has of course to have a sealed lid on top to prevent oxygen getting in otherwise all the charcoal will burn at once which would be bad.

The Heines translation of a manuscript of the Libellus de Alchimia does not mention athanor, although it has several furnace designs described. The first is clearly a draft powered calcinatory furnace, which will rely upon the addition of charcoal from above in order to maintain heat. The distillation furnaces are similar, apparently, the point being that they are draft furnaces built above a pit for the ashes to fall into and the air to be drawn up. The work dates to the 13/14th centuries.

The 15th century text, Wellcome MS. 446, found here: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ezvdv4um

Has a number of furnaces, but nothing like an Athanor. It seems to me that one would be required more for certain types of alchemical work than others, thus it would depend on the precise recipes you were using.

Ripley’s 12 gates in the 1591 Compound of Alchemy, to expand on the quote above, has more information:

When they be there, by little and little increase,

Their pains with heat, aye, more and more,

Never let the fire from them cease,

And see that thy furnace be apt therefore,

Which wise men call an Athanor,

Conserving heat required most temperately,

By which thy matter doth kindly putrefy.

So an athanor is a furnace that runs well for a long time and has good control of the heat. The issue here is does the 16th century version accord with the medieval version?

Turning to the late 16th century in England, we find The Key of Alchemy by Samuel Norton. On page 70 of the Hermetic Studies no. 9 edition of McLean, it says that “Yet note that when you shall take out of the earth this your glass, you must in an athanor give it a pretty fixing heat for nine days…”

i.e. the athanor appears to be a long term furnace with the ability to run constantly and perhaps at constant heat. In the MS there are 6 furnaces illustrated with number five having text beside it “the fifth is an athanor to calcine {symbol for ??} with an easier fire to dry it may be dissolved into lac virginis ?? is fed with ?? or ?? at a time.”

This particular furnace looks like a tall cylinder with a dome on top and the two openings, one for ashes at the bottom and one for feeding with fuel above it, then the cylinder rises up with a hole much further up, presumably for what is supposed to be in it. (Unfortunately the MS has not been digitised but you can see a picture of it on page 282 of Rampling’s book “The Experimental Fire”)

If we take this as being an authentic image of an athanor, we can look back at earlier works and see if there is anything which matches. Certainly nothing in Norton’s illustrations does, the key point being the cylinder which holds charcoal to feed the main fire.

However it does seem a bit different to the earlier furnaces, especially the third which looks more like what I would expect a long lasting Athanor to look like.

Which adds a little bit to the confusion.

If we turn to non-alchemical sources we get more information about athanors. To start with Biringuccio and his 1540 printed book, mentions them several times. He gives detailed descriptions on how to build one and attributes alchemist with coming up with ingenious complex furnaces capable of different heats.

They are also found in Lazarus Ercker’s work on running a mint and assaying metals.

So they seem to be found outside alchemy, but likely came from alchemy.

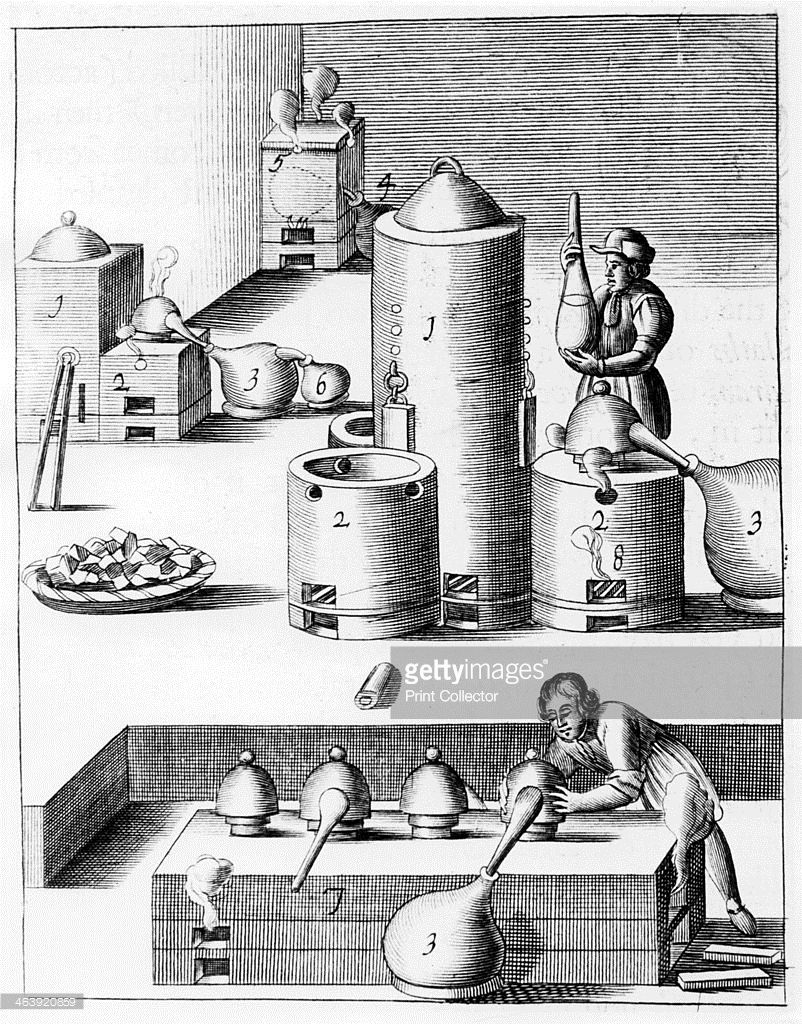

Here is an early modern image, stolen from pinterest, who knows where it comes from but the big central one marked J is what I am thinking of as an athanor:

In summary, athanor may well be a word that comes from Arabic, the problem is that I can’t seem to find specific examples of actual athanors before the 16th century, although at least Ripley mentions them in the 15th. They may well have existed before that, doing what later authors thing they do, but it is hard to be sure.